For reasons that boil down to my own naïveté and exposure to imperialist propaganda (better known as the American education system), I grew up assuming that entities like the United Nations and its member countries were infallibly dedicated to the welfare of human beings. That line of thought has since been killed, which makes Warehoused a sobering nail in the coffin. The new documentary from directors Asher Emmanuel and Vincent Vittorio infuriates and devastates by illuminating the woefully jammed gears in efforts to resolve the international refugee crisis.

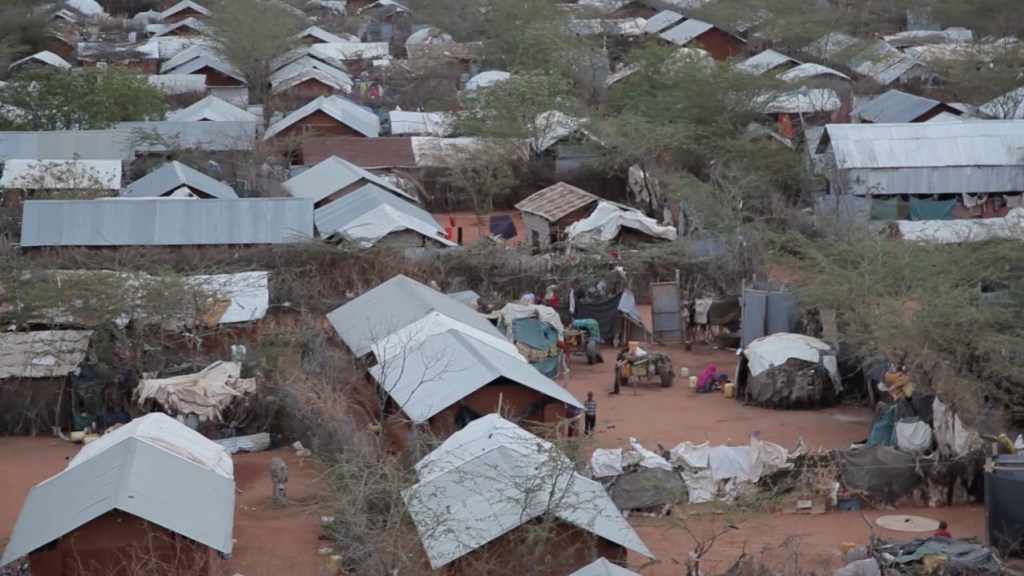

Over 12 million people live in refugee camps around the globe. Warehoused follows those who live in Dadaab, Kenya — the largest refugee camp in the world. The film’s title aptly summarizes the dehumanizing nature of what ultimately amount to storage facilities. Originally built for 90,000 refugees in the wake of the Somali civil war, Dadaab is currently home to roughly 350,000 registered refugees according to “official” counts (that’s roughly the population of New Orleans), although the actual number hangs somewhere around 500–600,000. That’s an intense figure to grapple with, one that featured interviewee and human rights activist Ben Rawlence establishes matter-of-factly within the documentary’s first ten minutes. To its credit, the film presents the facts and gets out of their way, relying on an impassioned but non-polemical approach to its subject matter.

Emmanuel (who also serves as editor) and Vittorio favor longer shots and even, rhythmic cuts. An opening credits sequence and a handful of other interludes break this pattern with smooth dissolves and animated montages as diagrams and statistics outline the disturbing extent of the problem. Original music from Lewis Hurrell augments already affecting sequences in subtle fashion, the string and piano ambience often only loud enough to be noticed. No-frills cinematography from Michael Amico and Alexander Falk renders Dadaab’s dry landscape in an unexaggerated washed out palette. The technical restraint aligns well with the film’s tight narrative scope.

Rather than attempt to encompass the entire sprawl of Dadaab, the documentary explores the stories of a few select individuals. Their testimonials are interspersed with insights from human rights advocates struggling to reverse the steadily worsening situation. The intimate method works in the film’s favor. It’s an effective piece of journalism because it unflinchingly unpacks something terrible without collapsing into maudlin condescension.

Near the end, Rawlence delivers a monologue about the importance of depicting refugees’ humanity, noting that it’s absurd to even need to remind viewers that refugees are both economic actors and, more importantly, human beings deserving of compassion. It’s a bizarre moment in which the filmmakers heavy-handedly imply their purpose. This misstep works against the understated ones preceding it, but doesn’t undermine otherwise emotionally staggering material.

As a friend (and feminist scholar) proposed to me when I described the film over coffee, Warehoused is the latest in a clear subgenre of activist-minded documentary whose efficacy feels increasingly uncertain in a cultural moment like this. Considering that many domestic political debates come down to one large group’s frightening lack of concern for another, it’s disheartening but sadly unsurprising to a film that assumes its viewers don’t care about this international human rights disaster. That the film evidently assumes such callousness in its viewers makes a terrible amount of sense in a society where there’s an active debate on whether or not to eliminate millions of people’s healthcare coverage.

Refugees in the camps don’t have the right to work, so the UN keeps them alive with meager food rations; resettlement into safer places is stymied by red tape. Emmanuel and Vittorio lay out these problems systematically, but the film frequently comes down to hand wringing over the political barriers to resolving the crisis. This is also the directors’ solution to the problem: perhaps building concern for our fellow human beings is the first step forward. For that reason, the moments in the film that overtly cloy for empathy do so necessarily.

Late in the movie, 29-year-old Liban Rashid — a young man who spent over two decades in Dadaab — pitches a story to a representative from a media nonprofit called FilmAid. Rashid wants to honestly depict Dadaab’s people through film. His intention to engender empathy, like Emmanuel and Vittorio’s, is noble. But I felt as hopelessly despondent watching his pitch as I did while watching the rest of the documentary.

Rhetoric around resolving humanitarian issues often laments a lack of empathy as the root problem, but I would argue that apathy is the true culprit. Modern news media allows us to so frequently see people suffer and die to the point of total desensitization. There are people working to reduce mass suffering, but the overstimulation and fragmentation of our culture often leaves us only worried about our own problems. Therefore storytelling that aims to activate an audience’s empathy often doesn’t translate into action.

Whether it means to or not, what Warehoused does best is illustrate the dearth of compassion that necessitates its existence, and the ease with which those rendered empathetic may still shrug it off.

Verdict: Movie Win

~ Nathan